#Mellel continues footnote free

Then, I move the text to Word/Writer for polishing up, so it's not like I broke free from heavy word-processors. Markdown offers many advantages (longevity, simplicity and openness), but so far I have been using it for a first pass in my writing. The last thing you need hours before a deadline is discovering you have to handle hundreds of citations manually. Relying on Pandoc adds a layer of complexity and incompatibility with Zotero's addons for Word/Writer, and the markdown file doesn't itself contain the rendered citations. It is very easy to use, and it looks a whole lot tidier than any of the alternative fonts that I found.I am using Obsidian for academic note-taking and cross-linking, and I am considering also doing my writing in it, but I am not quite sure if this is a good idea or a rabbit hole. My next class is on Thursday and I hope to be able to add to what I have written here then in the meantime, if anyone would like Ugaritic fonts then I can recommend the work of David Rosenbaum, the creator of the font that I am using. If anybody has any suggestions then I am all ears. Of course, I could be very much mistaken. As for the final line, unless I am mistaken this looks like a formulaic closure, related to the root √גמר. We also have what appears to be ‘one hundred’ in the second last line. We have ‘seven’ written three times (twice as part of a longer word lines 1 and 6), ‘ten’ three times (lines 3, 6 and 9), ‘five’ twice (lines 4 and 5), ‘four’ once (line 8), and ‘eighteen’ once (line 2). So, what does it all mean? Well, the obvious words are the numbers. With English letters, the above text would be transcribed: This is because the Ugaritic alphabet had three different representations of this letter, corresponding to אַ, אִ and אֻ.

You will notice that the alephs all have vowels beneath them. With Hebrew letters, this text reads as follows: The transcription, as it appears above, is my own and may therefore be a misreading of the actual text in question. They do not always appear where we might want them, and their presence can sometimes also be mistaken for a gimmel (such as is found as the second letter of the final line).

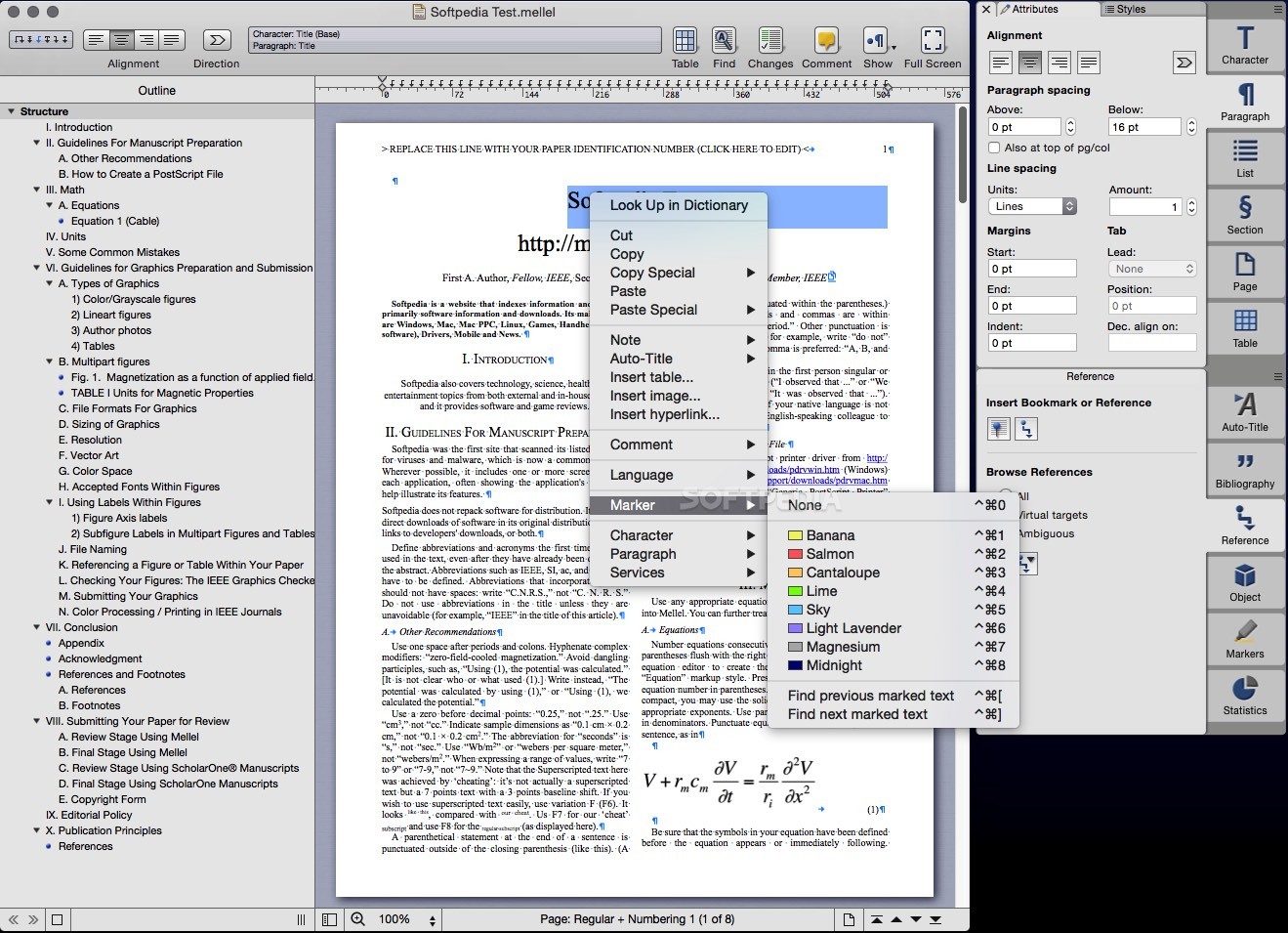

The short vertical strokes found throughout the text (such as between the third and the fifth letters of the first line) are actually word-dividers. As my fonts were not able to produce that symbol, I have unwillingly omitted it here.Īnother quick note, before we move to the transcription. In our text it is written in minature and placed slightly to the right and beneath the letter in question. It looks like the Akkadian /a/, used in Babylonian texts (along with the plural determinative) as the logogram for ‘water’. One sign here has not been reproduced by me and that is from the fourth line, written (seemingly) as a ligature with the sixth symbol. The letters themselves are not too dissimilar from the letters of the Arabic alphabet, and are even believed to have existed in an order that was utilised for certain types of South Arabic and partly, I was interested to note, Ge’ez. Pretty, isn’t it? Well, while it might look complicated, the alphabet is actually rather simple: the difficulty lies in simply recognising the signs on the tablet. Seems that, of the many languages that WordPress might enable one to use, Ugaritic is not one of them. If anybody has any suggestions as to its meaning (it looks like a list of items to me, perhaps an inventory), then I welcome your opinion! Due to font problems, I have typed it up on Mellel but have attached it here as a picture. In order to demonstrate this, I have decided to post a short text in Ugaritic, about which I know absolutely nothing. Unlike many other ancient languages, Ugaritic is still very much open to interpretation. As mentioned, I have just started studying Ugaritic at Sydney University.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)